Saints - Arunagirinathar

By N.V. Karthikeyan

Introduction: Saints - Arunagirinathar

By N.V. Karthikeyan

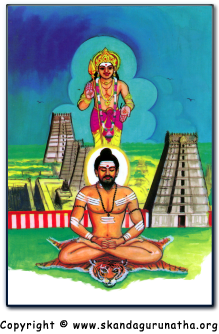

The Kaumaras — those who regard and worship Lord Kumara, Skanda, Shanmukha, or Karttikeya as the Supreme Being — are one of the six sects of Hinduism. Saint Arunagirinathar is revered as one of the foremost among the acharyas (spiritual teachers) of the Kaumaras. He lived at Thiruvannamalai — the Agni Kshetra — one of the Pancha Bhuta Sthalas, which is sacred and famous for many other reasons as well.

As is the case with most of the saints and sages of the past, no authentic record of Arunagirinathar’s life is available. Nothing definite is known about his birth, caste, etc. This has naturally led to much speculation about his life. And today, we have a number of versions of Arunagirinathar’s life and that too with countless variations in minor details. When one goes through them, one is at a loss to know which is right and which is not.

The more one reads, the more confusion is created in one’s mind. I say confusion because different authors say different things without any source, basis, or authority, except their love for the Lord and the Saint. Even the few books that I could obtain and go through made me feel that I better leave this subject (i.e. the life of Arunagirinathar) untouched, lest I should add to the confusion which is already there enough. But, at the same time, I could not help writing something about Arunagirinathar’s life, as I felt the book would be incomplete without the illustrious Saint’s life, especially this being the only English rendering of “Kandar Anubhuti.” Hence, I have tried here to collect and consolidate only those versions which have some reliable sources under three headings (listed below) — with, of course, some stress on the view that appeals to me as more intelligible, reasonable, and supported by some kind of evidence. I leave it to the readers to take what appeals to them. Whatever it be, one thing is certain — that Arunagirinathar was a saint of no ordinary attainment as could be assessed from a study of his different works.

LIFE OF SAINT ARUNAGIRINATHAR

- Traditional account

- Historical account

- Internal evidence account

Traditional account

This has come down to us through generations by way of hearsay. This is mostly based on the earliest written poetic work on the life of Arunagirinathar entitled, “Arunagirinathar Swamigal Puranam” by a saintly Swami — Thandapani Swamigal — who also goes by the names of Murugadasa Swamigal and Thiruppugal Swamigal (1839-1898). He composed the puranam about Arunagirinathar about the year 1865. It is as follows:

Arunagiri was born in Thiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu, and is believed to have lived in the middle of the fifteenth century A.D. He was the son of a Daasi (a dancing girl) named Muthu and had an elder sister by name Adhi. It is also said that Arunagiri was born to Muthu from the famous mystic saint of Tamil Nadu, Pattinathar, in an unusual manner.

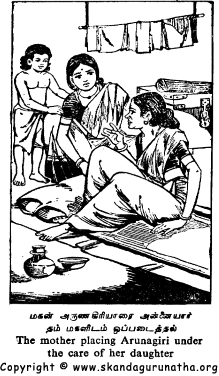

When the boy attained the age of five, he was put to school. At his seventh year of age, his mother passed away. She loved the boy so much that while she was in the death-bed, she entrusted Arunagiri to the care of her daughter (i.e., the elder sister of Arunagiri) with specific instructions not to do anything that would displease him. Arunagiri’s sister understood the anxious mental condition of her mother and gave her a word of promise that she would leave nothing undone to please Arunagiri and keep him happy.

As Arunagiri grew in age, he found the company of women more pleasing than his studies, which he virtually neglected and sought the pleasures of enchanting courtesans. Slowly, he became a confirmed debauch.

His sister, who came to know of this conduct of Arunagiri, tried her best to extricate him from the traps of public women. But nothing could prevent Arunagiri from his infatuated love for women. He must have his ways at any cost.

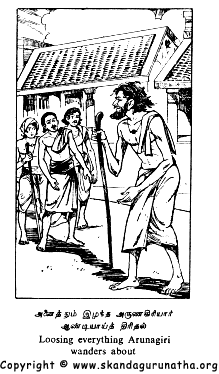

The poor sister could not do anything drastic, lest she should be harsh to Arunagiri or displease him, which would mean breaking her promise to her mother. Thus, did Arunagiri indulge in sex heedlessly and depleted all the wealth hoarded by his mother.

Slowly, he began to snatch away, one by one, the ornaments of his sister, sometimes with her knowledge and sometimes otherwise. The helpless lady could do nothing except pray to the Lord to save Arunagiri.

In the meantime, Arunagiri contracted many diseases and suffered much. Yet he would not learn a lesson. He squandered all his sister’s wherewithal and left her a complete pauper. But he would yet demand money from her to satisfy his sexual appetite and if she pleaded helplessness, he would threaten her of sinking before her very eyes.

In spite of her being reduced to this most pitiable condition, she could not imagine displeasing Arunagiri. But, now she was utterly helpless. She grew desparate and said, “Brother! I had been helping you with all that I had. But now I find no means to help you. Yet I cannot think of displeasing you. Brother, tell me what can I do? Well, only one means is left now. Though we are born of the same mother, our fathers are dfferent. Hence, the pleasure that you seek from a woman, you can find with me!”

She would have continued, but her throat choked; she became silent.

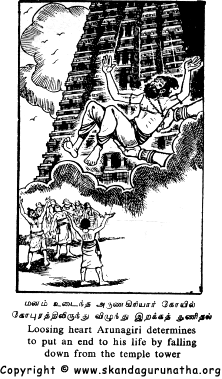

Lo! These words entered Arunagiri’s heart like sharp arrows and shook his very being so fundamentally that he repented with a contrite heart for all his past misdeeds and wept bitterly. And in a moment he decided to put an end to his life as an expiation for all the sins committed by him.

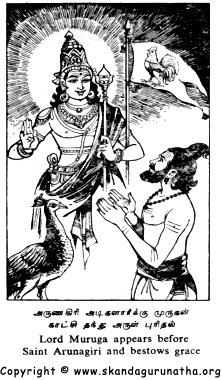

Before his sister could understand as to what was happening to Arunagiri, he ran posthaste, climbed the tower of the Arunachala Temple, repented with an honest feeling, cried aloud the Name of the Lord, “Muruga! Muruga! Muruga!” and jumped down, to put an end to his miserable existence and thereby be freed from his sins.

Who can understand the ways of the Lord! Ere Arunagiri fell towards the ground, when there stood the Lord with His outstretched hands and held Arunagiri in His warm embrace. Yet, Arunagiri knew not anything.

Transliteration:

muthai-tharu pathi thiru-Nagai

athi-kiRai sathich-saravaNa

muthi-koru vithu-guru-bara …… enavOthum

Meaning:

See Also :

The Lord then disappeared. Arunagirinathar stood there totally transformed. He adopted the life of a renunciate. The erstwhile sinner shone now as a saint. His body was cured of all its diseases; his mind was purged of all impurities; his heart was brimming with devotion and he was in a highly ecstatic mood.

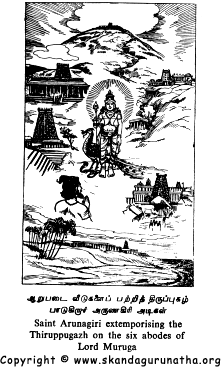

Arunagirinathar, having now got the complete grace and command of the Lord, at once completed the song. He was full of expression, love, and supreme devotion. As the waters of a reservoir rush forth when the floodgate is thrown open, wisdom and love flowed through the Saint in the form of Thiruppugal songs.

Arunagirinathar went from tower to tower of the Arunachaleshwarar Temple and poured forth poems in exquisite Tamil.

He then went round the streets of Thiruvannamalai, singing the glories of the Lord in diverse ways. He was God-intoxicated out and out, and started on a pilgrimage to all holy places, singing the Thiruppugal (“Glory of God”), wherever he went, enjoying various kinds of divine experiences at different places.

Next the author recounts the “historical” version of the Life of Arunagirinathar below (using sanskrit works, historical inscriptions around Thiruvannamalai, etc).

Historical account

In his work, “Sansana Tamizh Kavi Charitam,” Rao Saheb M. Raghava Iyengar, has given a detailed account of his researches, with appropriate authorities, based on certain Sanskrit works and inscriptions around Thiruvannamalai which reveal many interesting facts about the early life of Arunagiri. The salient features of his research may be summarized as follows:

It is almost an accepted fact that Arunagiri belonged to the time of Villiputturar, the author of the Tamil Mahabharatam. Villiputturar lived during the same time as the Irattaiyar (the twin-poets) whose period is the middle of the 14th century.

Arunagirinathar, in his Thiruppugal, refers to two persons — (1) Pravudadeva Maharaja (a king who ruled during Arunagirinathar’s time); and (2) Somanathan (the head of a Mutt). Based on Arunagirinathar’s description of the political condition prevailing then, it can be assumed that the king referred to by Arunagirinathar should be Pravudadeva Raya II, who ruled during the earlier part of the 15th century. As regards the time of Somanathan, he is believed to have lived about 1370 A.D., based on an inscription in the wall of the Siva Temple at Puttur. It is also ascertainable that the said Somanathan was one of the foremost among the Sivacharayas — learned Vidvans and Gowda-Brahmins — who came from North India and settled at Mullandiram and Devikapuram sometime earlier. Considering the above data, the author concludes that Arunagirinathar’s time should be between that of Pravudadeva and Somanathan, i.e., between the close of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century.

From other inscriptions, it is learnt that from amongst these Gowda Brahmin scholars and Pandits, some were talented Sanskrit poets called, “Dindima Kavis.” Historians*** hold that our Arunagirinathar is a descendent of these Dindima Kavis and he is himself referred to as such in one of the Sanskrit works of his posterior entitled, “Saluvabhyudayam,” who says that his father, Arunagirinathar by name, was a “Sarva-Bhauma Dindima Kavi,” an “Ashtabhasha Paramesvara,” a past master in compositing Chitra Prabandha, and one greatly revered by the three Tamil kings: Chera, Chola, and Pandya. Sri Raghava Iyengar proves, from internal evidences and coincidence of time, place, etc., that the Arunagirinathar referred to in the above Sanskrit work is our Arunagirinathar, the author of Thiruppugal, etc., works.

*** Most prominent among them being the late Sri T.A. Gopinatha Rao who has published a lengthy article in the “Indian Antiquary” of 1918.

Further, there is an inscription of 1550 A.D. in the Siva Temple of Mullandiram, which records the gift of a piece of land by a Brahmin lady to erect a small altar to “Annamalai Natha” inside that Siva Temple. This lady is said to be a descendent of the Dindima Kavi Annamalai Natha. It is believed that the Annamalai Natha, in whose memory the altar was built, is our Arunagirinathar, because Arunagirinathar, being a divine-inspired poet and saintly soul of an extraordinary calibre, became so famous that many temples came to be dedicated to him and one of his descendants donated for one such in his very birth place, Mullandiram. From all these, it is proved and held that Arunagirinathar belonged to a Brahmin family of Mullandiram near Tiruvannamalai.

One objection to this view is: though Arunagirinathar is referred as Dindima Kavi, etc., in the Sanskrit work of his son (to which facts there are corresponding internal evidences in the works of Arunagirinathar), Arunagirinathar’s greatness was not so much due to these factors but was due to his extraordinary devotion to Lord Murugan and his innumerable compositions of Thiruppugal songs, to which there is no mention in the Sanskrit work. This objection does not seem to be a serious one because when a person is referred to, all aspects of his life need not necessarily be mentioned. So long as the facts mentioned about Arunagirinathar in the Sanskrit works do not contradict any of the facts available about him, it can be safely taken as authentic, for no description of a person can be complete. That he was an expert in composing as a Chitra Kavi, that he was a Dindima Kavi, and that he was revered and worshipped by the three kings — all which are fully relevant to Arunagirinathar — are facts which can be substantiated from his Thiruppugal and other works. Again, if all these do not refer to our Arunagirinathar, who is he that is referred to by these? There seems to be no one else of that time period to whom all these can be attributed. To simply say that these do not refer to our Arunagirinathar would be a meaningless objection unless the existence of another person to whom these refer can be proved. It cannot be that someone else was, who was such a great poet as to be called as Dindima Kavi, expert in composing poems as a Chitra Kavi and worshipped by the great Tamil kings and yet whose name or life-history or any of his works is not available on record. If these were really to refer to such a great person other than Arunagirinathar, something about him or at least some of his works must be available for reference, somewhere. Hence, in the absence of any such thing as this, these details may be taken, in all probability, to refer to Arunagirinathar, the author of Thiruppugal and other works, and it can be safely regarded as such.

Next the author recounts the “internal evidence” version of the Life of Arunagirinathar below (using the primary works of Arunagirinathar: Thiruppugal, Kanthar Anubhuthi, etc.).

Internal evidence account

The internal evidence account is the story of the Life of Saint Arunagirinathar told from Arunagirinathar, himself. The details of his life have been drawn from an in-depth study and analysis of Arunagirinathar’s various works (Thiruppugal, Kanthar Anubhuthi, Kanthar Alangaaram, Kandar Anthaathi, Thiru Vaguppu, Vel Virutham, Mayil Virutham, Sevval Virutham, and Thiru-vElu-kootru-irukai) wherein his personal experiences, confessions, and truths were revealed. The internal evidence account is likely the most accurate version of the story of Arunagirinathar’s life because it is told from the perspective of Arunagirinathar himself. One must keep in mind that the other two versions of Arunagirinathar’s life, namely the traditional account and historical account, are more susceptible to the personal biases of the story-teller and historian, respectively.

[NOTE: The in-dented information that follows hereon after is a collection of references used by the author to give the internal evidence account of Arunagirinathar’s life — either supporting or disproving facts about the Saint’s life.]

The internal evidence account of Saint Arunagirinathar’s life is based on Rao Bahadur V.S. Chengalvaraya Pillai’s Tamil work, “Arunagirinathar: Varalaarum Noolaaraychiyum (Arunagirinathar: Life and research on his works),” published in the year 1947. Our revered and scholarly Pillai Avl, has done a tremendous work, a novel and original thought of his, in codifying the “Murugavel Panniru Thirumurai” corresponding to the “Saiva Panniru Thirumurai,” for which we are indebted to him. According to his research based on internal evidences of the Thiruppugal and other works of Arunagirinathar, the life of the saint, in his above work, is thus:

Apart from the fact that Arunagiri lived in Thiruvannamalai during the time of Pravuda Deva Maharaja, who ruled that territory in 1450 A.D., (already mentioned in “historical account”), no internal evidences are available as to say anything definite about Arunagiri’s caste, his parents, and his early life.

Arunagiri was acquainted, even from his boyhood, with the earlier Tamil works, such as the Thevaara, Thirumanthiram, Thirumurugaatruppadai, Thirukkural, etc. He had the skill and capacity to compose poems and he was a devotee of Lord Murugan.

As fate would have it, Arunagiri fell a victim to the evil traits of courtesans and lost all his property in debauchery. Utilizing his talents of composing extempore songs, he earned wealth only to please his paramours. He was finally over-powered by poverty and many diseases took heavy toll of him, and he felt ashamed over his own plight.

Realizing his condition and also the meritorious deeds of his earlier lives, an elderly pious person appeared before Arunagiri and advised him to do penance and contemplate on the six-faced Lord Shanmukha. But, Arunagiri paid no heed to this saintly instruction and wasted his life for some more time, only to be ridiculed by his kinsmen and townsmen.

But, time is a great healer. The time for fruition of his past meritorious deeds approached and his mental attitude, too, underwent a change. He repented for his ill-spent life and for not having acted up to the advice of the pious person. He, therefore, offered up a prayer to Lord Murugan, sat near the big tower (Gopuram) of the Arunachaleshwarar temple at Thiruvannamalai and commenced sadhana in right earnest, but to no effect. He then decided upon a plan, that putting an end to his life, and to this end he climbed the temple-tower and dropped himself down.

Lord Murugan, whose eternal slave he was, held Arunagiri in His arms and saved him from death. The Lord then gave Arunagiri His Darshana – being surrounded by His devotees, veda-chants resounding, and dancing of His peacock. The Lord addressed him as “Arunagiri-Naathar,” showered His side-glance grace, granted feet-touch, wrote His six-lettered Mantra on Arunagiri’s tongue, and imparted knowledge of the Tamil language in its three aspects of prose, poetry, and drama. He also gave Arunagirinathar a japa-mala (rosary), removed his Mala (karmic dirt) and Maya (ignorance), gave Mowna-Upadesa, taught him the different Yoga-paths (techniques), imparted upadesa on jnana-marga, and revealed the highest secret of Pranava or Omkara. The Lord then commanded Arunagiri to sing His praises and, when the latter pleaded his ignorance, the Lord Himself gave the first line as “muthai-tharu…” and ordained Arunagirinathar to sing, thus, which, with the grace of the Lord, Arunagiri completed in no time.

Finally, Arunagirinathar attained the highest state of Sayujya — the Advaitic realization of being one with the Almighty Lord Skanda (Parabrahman). Thus, did Arunagirinathar live a glorious life of God-consciousness, exhibiting many a super-human deed, lifting people from the quagmire of samsara (cycle of birth-death-rebirth) and planting them firmly in the awareness of God; and the Saint continues to guide seeking souls to perfection, lending them the needed support, even today. May the grace of Saint Arunagirinathar be upon us all, always!

It is worthwhile to record that our revered and late Sri V.S. Chengalvaraya Pillai has quoted authorities for each and every one of the facts mentioned above from the nook and corner of Arunagirinathar’s works and also from other sources, which all reveal Arunagirinathar’s high scholarship, deep knowledge and devotion to God. However, it is astonishing to note that Pillai has knowingly omitted certain facts, which of course, he has admitted in the very preface itself. He says:

As we cannot with any certainty say that the printed Thiruppugal songs are Arunagirinathar’s own words; and as it was the wont with the Tamil saints to depict themselves as being caught up in Maya, though really unaffected by it, for the sake of teaching to the world, I have consciously omitted even certain internal evidences afraid of quoting them as referring to Arunagirinathar’s life, as for instance:

1. In Thiruppugal verses***** 392, 752, 1301, though Arunagirinathar’s words are clear to prove that he led a life (of Grihasta) with wife, children, sister-in-law and other relatives, yet hesitating to boldly state as such I have omitted the same.

2. (a) As regards Arunagirinathar’s caste, he condemns himself in T. No. 26***** as a “low one who avowedly consumes meat.” From this, can one say he belongs to a meat-eating caste? And again, in verse 31 of the Kanthar Anthaathi, Arunagirinathar himself says, “O Brahmins, who mercilessly kill goats and do Yagas or sacrifices!” Is he, who thus condemns Brahmins (of their acts of killing of animals), one belonging to the meat-eating caste?

(b) Further, in his work, “Sasanat Tamizhkavi Charitam,” Rao Saheb M. Raghava Iyengar refers to Arunagirinathar as “Sarva-Bhauma Dindima Kavi,” “Ashta-Bhasha Paramesvara,” etc. Now, if we propose to claim Arunagirinathar to be a Brahmin because there is a lot of the usage of Sanskrit language in his Tamil works, (it cannot be; since) we are led to think that one who had obtained “countless powers” due to the special grace of Lord Murugan, should the use of Sanskrit language present any difficulty?

*****T. No. refer to the Thiruppugal numbers in the author’s work, “Murugavel Panniru Thirumurai.”

To avoid these confusions, I have stated that Arunagirinathar’s caste is unknown, being satisfied that he is a great Tapasvin and a Knower of Truth, concludes Sri V.S.C. Pillai.***

***As I had no occasion to study the Thiruppugal songs earlier, when I read this preface of his, I was eager to have a first-hand knowledge of what Arunagirinathar says in the songs referred to in the preface as well as in all the other Thiruppugal songs. I, therefore, felt it was necessary to glance through them, at least, and in doing so many facts were revealed.

Now, let us consider the above points.

1. A free rendering of T. No. 392 would be:

Wife ridiculing, all townsmen ridiculing, all women-fold ridiculing; father and relatives;

Dejected in mind, I also dejected in heart, all people thoughtlessly using condemning words and speaking low of me;

Darkness enveloping my pondering mind, I thought “Is this the happiness of my having taken birth?”;

And reflecting thus daily, when I decided to cast the soul off from this body – those feet that you granted then, O Lord grant me again;

The song begins with the words, “wife-ridiculing.” While the ridicule of his wife, father, relatives, etc. is the cause of Arunagirinathar’s taking a decision to put an end to his life, Sri Pillai has taken the effect as an authentic information but ignored the very cause itself. In a song of this type, to take some facts as relevant and cast away some others as irrelevant, and that too, to ignore the cause-factor and accept the effect, neither seems to be rational nor brings soundness to one’s research.

Moreover, the facts that Arunagirinathar decided to end his life, that he knew the different earlier Tamil works, etc. are supported by a few authorities only. While these facts can be taken as relevant to Arunagirinathar’s life, why not also take that Arunagirinathar was married, had a wife, children, mother, father, and relatives – a fact that Arunagirinathar says in unambiguous terms in not less than 30 places, i.e., in his Thiruppugal poems as well as in his other works.

Further, it is said that it was the wont of great Tamil saints and poets to take upon themselves the shortcomings of the masses, repent for such low acts and invoke the grace of God to condone their evils and shower His blessings; and this method they adopted as an effective means of transforming people, as the poems are given in first person, capable of touching the hearts of people when they recite them. It is, therefore, held by many that the shortcomings depicted by Arunagirinathar in Thirupugal songs need not necessarily refer to him and should not be taken literally. Sri V.S.C. Pillai also contributes to this view, and there is some truth in it. But he seems to have forgotten the important point that this view is advanced primarily to relieve Arunagirinathar of such evils as debauchery, etc., and not so much to deny that he was a householder; because while prostitution is an evil and sin, Grihasthasrama (state of householder) is not an evil, crime, or shortcoming. On the other hand, Grihasthasrama is a praise-worthy stage of life, more so according to the Tamil scriptures. It is, therefore, really ununderstandable that, while contributing to the above view, Sri Pillai should accept that Arunagirinathar indulged in prostitution but not be prepared to accede that he led a householder’s life. When remote and vague internal evidences are given due authenticity to support even minor facts, what is the harm in accepting that Arunagirinathar led a family life when there are umpteen evidences for the same? Will it diminish Arunagirinathar’s greatness? Or can we add an inch to his greatness in ignoring this fact? Perhaps to accept that he had wife and children might lend support to the acceptance of that fact that Arunagirinathar’s son has referred about Arunagirinathar in one of his Sanskrit works and that a descendant of Arunagirinathar has donated for the construction of an altar for him at his native village Mullandiram, – facts which are proved by historians based on inscriptions, etc. (as seen earlier)! Is it not strange that he who, setting aside the traditional and historical accounts, has set forth to write the life of Arunagirinathar based mainly on internal evidences should ignore certain vital facts of life so conspicuously disclosed in his works!

Here we can have a useful and pertinent diversion to see how far this view is right – the view that what Arunagirinathar has portrayed of himself in the Thiruppugal songs do not refer to him, that he never led an evil or sensuous life (including a family life), and that his early life was pure and unblemished.

It is true that great men take upon themselves the evils of the general masses, and Arunagirinathar, too, has done so in some Thiruppugal songs with the intention of educating and reforming the evil-doers. This can be evident from such songs as T. No. 121: “Seeralasadan”; T. No. 180: “Thitamili”; T. No. 183 “Pancha Paadagan”; T. No. 576: “Pulaiyanaana”; T. No. 611: “Avaguna Viraganai”; T. No. 291: “Thaakkamarukkoru”; T. No. 363: “Maalaasai Kopa”; etc., wherein he condemns himself in general terms – as a sinner, an egotistic person, a fool, a good-for-nothing person, an uncultured, an unlettered, etc. , etc., – and prays to the Lord for His grace. Such poems are depictions, no doubt, because the evils mentioned in these are of a general nature. Also, there are poems which can prove that he was well-versed in the earlier works of the Tamil and Sanskrit languages, that he was cultured, that he had practised Tapas in his earlier births, etc., all which will be contradicted if the above verses are to be taken literally. Since the condemnation in these Thiruppugal songs is of a general nature, we can easily take these poems as depictions and not literally as referring to himself.

The Murugan that Arunagirinathar manifested was not so much the theological God but the Supreme Reality that is behind the different manifestations. Hence, there should be no question of the Devi holding Skanda somewhere in Kailasa. It does not, whoever, mean that one God is inferior or superior to another. Every manifestation of God has different aspects; at least two – the Absolute and the relative. Lord Krishna was not merely the friend and charioteer of Arjuna but also the Bhagavan or Supreme God who gave Gita-Upadesa as also showed Arjuna the visvarupa. Similar is the case with all Gods – Lord Skanda, Devi, etc. The Lord is all aspects at once and it is the attitude of the devotee with which the Lord is invoked, viz. Sattvika, Rajasika or Tamasika, that determines matters.

Arunagirinathar had pure devotion and his invocation was not motivated by personal ends, while that of Sambandandan was prejudiced and motivated. This accounts for the spontaneous manifestation of Lord Skanda and the non-appearance of the Devi, respectively. God is a slave of the devotee’s love, whichever be the form, and whoever be the devotee. The incidence only proves the greatness of Arunagirinathar and his pure love for God, which was equally great towards the Divine Mother, too, as can be seen from many of his Thiruppugal songs. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that Arunagirinathar had the blessing of the Divine Mother, too.

Under such circumstances to say that the Devi was holding fast to Murugan preventing Him from coming to the assembly would at best disclose one’s inadequate understanding of Arunagirinathar’s love for Murugan as also his concept of God, which was one of the spiritual Reality behind everything. That is why Arunagirinthar says in the above Thiruppugal, “O Lord! Come dancing so that when You dance, Siva, Vishnu, Brahma, Kali, etc., – everything dances!” When such is the prayer, if Kali were really to hold fast to Murugan, Arunagirinathar’s prayer would have manifested not only Murugan alone but would have brought Kali, too, with Him.

When Arunagirinathar manifested Lord Skanda and the king had Darshana, it is said that the king lost his eye-sight due to the divine brilliance which human sight cannot endure. At once, Arunagirinathar gave Bhasma (vibhuthi/holy ash) and brought back the king’s eyesight. This is one version; while the other is that Arunagirinathar fetched the Paarijaatha flowers from heaven and restored the king’s vision. It is thus:

Having defeated in the contest, Sambandandan disappeared from the assembly in utter shame and left the kingdom. But his enmity to Arunagirinathar did not subside. He somehow wanted to do away with Arunagirinathar and so, after sometime, he approached the king again. Knowing that the king who had lost his eye-sight would be eager to get it back somehow, Sambandandan said to the king: “O mighty king! There is only one way of getting back your eye-sight. If the heavenly Paarijaatha flowers are brought and placed over your eyes, they will regain vision. And this super-human act, only Arunagirinathar and myself are capable of doing. But I wish that Arunagirinathar do it, as my bringing the flowers will affect his fame and glory. Please, therefore, request Arunagirinathar to fetch the flowers and in case he declines to do so, I shall at once bring them for you.”

The king, not knowing Sambandandan’s evil intentions but desirous of regaining his vision requested Arunagirinathar accordingly, to which the latter readily agreed. Arunagirinathar climbed the temple gopuram (tower) left his physical body there, entered the body of a parrot that was just dead then, and flew to the heavenly region. It is said that he did this as one cannot go to heaven with this Panchabhuta-Sarira (or body made of five elements).

[But, strangely, the parrot’s body, too, is made up of the same five elements!] Sambandandan took this opportunity and informed the king that Arunagirinathar is dead, that his body lies in the Arunachala-Gopuram and that it should be burnt soon. The king, too, without due investigation or thought, ordered it to be cremated, which the evil-minded Sambandandan got done without the least delay, lest Arunagirinathar should come back.

The Arunagirinathar-parrot returned from heaven with the Paarijaatha flowers only to find his body missing from the Gopuram. Taking it to be the will of God, the parrot went to the king, offered the flowers to him and, to his great joy, restored the king’s eye-sight. The king felt extremely sorry for his hasty and unconsidered action in getting Arunagirinathar’s body burnt. He wept bitterly and begged the Saint’s pardon. The Arunagirinathar-parrot, his divine mission being over, flew away and seated itself on the arms of the Lord, for eternity.